After the 7th New York’s baptism of fire at the Alsop Farm, the regiment passed through a hard week of desultory fighting at Milford

Station, North Anna River, and Totopotomy Creek. Lieutenant Frederick W.

Mather, an officer attached to Battery L, later wrote that these engagements weren’t

worth chronicling except that, “in the 10 days, from Sunday May 22, we had been

under fire many times, and had lost one officer and 31 men killed or died of

wounds, one officer and 86 men wounded, and 16 men missing, making a total loss

of 135; as great a loss as some regiments sustained at Gettysburg.”

Although they had been part of the Army of the Potomac for

exactly two weeks, the heavy artillerymen of the 7th New York comprehended the bitter reality

of the Overland Campaign. To complete their mission, they would have to fight dearly for every inch of

ground. Surgeon James E. Pomfret, wrote home, “From this point we shall have to

fight our way to Richmond foot by foot. Every hill is contested and every road

fought for, but we are steadily advancing.”

But unfortunately, at the next battle, the Army of the Potomac did not

advance steadily.

On the evening of June 2, the 7th New York

accompanied the Army of the Potomac’s 2nd Corps during its exhausting night

march to Cold Harbor, a dusty crossroads in Hanover County, Virginia. Ahead of the bluecoats, Lee’s legions had built miles of formidable entrenchments, obstructing the Union’s line of

advance. Believing that Lee’s men were on the verge of collapse, Grant ordered a

frontal assault with three of his infantry corps. The commanders of 2nd, 6th,

and 18th Corps received orders to strike the enemy line at dawn, June 3.

The corps and divisional commanders expected to use their colossal, new regiments in the first assault wave.

For the 7th New York, it meant another chance to prove to the

veterans of the Army of the Potomac that heavy artillerymen knew how to fight.

Along with the rest of the 2nd Corps, the 7th

New York Heavy Artillery arrived at Cold Harbor after midnight, June 3, and

without taking time to bivouac or build entrenchments, the soldiers flopped themselves onto the fields east the Miles Garthright house and went to sleep.

One of those exhausted men who fell fast asleep was First Lieutenant

Frederick W. Mather. Mather was born on August 2, 1833, at Greenbush, New York.

Prior to the Civil War, he lived in Wisconsin, eking out a minimalist existence as a hunter and trapper. After

his wife died in 1861, Mather returned to his home state and enlisted in the Union

army. After the call for “300,000 more,” he went to Albany to join the 113th

New York. Whether by accident or design, he enlisted on his twenty-ninth

birthday, August 2, 1862. In April 1864, long after his regiment had been

re-designated as heavy artillery, he received a commissioned to first lieutenant of

Battery L.

When Mather awoke during the predawn hours of June 3, 1864,

he discovered that his regiment had disappeared. While he was asleep, the 7th

New York—and the entire division with it—had marched south along the Dispatch

Station Road where the corps commander, Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, positioned it to spearhead the assault against the Confederate earthworks near the McGehee farm. Frantically, Mather searched for his missing unit.

Luckily, a freed slave happened to notice where Brig. Gen. Francis Barlow’s

division (to which the 7th New York belonged) had gone. Rushing

southward, Mather found his unit in line of battle, just minutes away from receiving the order to charge. When he arrived, Mather apologized profusely to his battery

commander, Captain James Kennedy, for sleeping through the “fall in” order.

As he apologized, Mather saw the corps commander, Maj. Gen. Hancock, consulting with his two divisional commanders, Brig.

Gen. Barlow and Brig. Gen. John Gibbon. Hancock explained, “General Barlow, you

will carry the enemy’s works, and General Gibbon, you will support General

Barlow.” It was then that Mather wished he was still asleep. He realized his regiment was about to lead the Army of the Potomac’s latest assault. He

recalled what happened next, “It was beyond the gray of the morning, but not

quite sun-up, when we moved through the thin strip of woods, and, coming into

the open, saw the enemy’s works, and with a hearty cheer we charged them.”

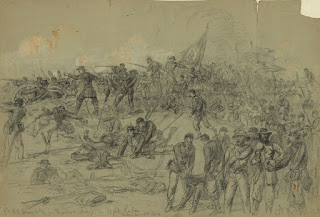

Moving west over the Dispatch Station Road, the soldiers of

the 7th New York Heavy Artillery saw a redoubt crowning the top of a steep

knoll. This was Edgar’s Salient, occupied by the 26th Virginia

Battalion and Captain William Caskie’s Virginia battery. The enemy gunners savaged the New Yorkers as they clambered toward the redoubt. Thrice,

the 7th New York’s color bearer fell, and each time, the flag was

picked up by a new volunteer. A piece of shell struck Mather’s scabbard,

destroying it, and another bounced off his left hip, spinning him around. It

left behind an ugly bruise, but otherwise, it did not disable him. “The air seemed buoyant

and we were flying!” recalled Mather in 1896. “The hill became so steep that

the grape and canister they were giving us went over our heads with a ‘swish,’

much as a charge of fine shot goes among a flock of blackbirds.”

In the next instant, the New Yorkers were on top of their

foe. Hand-to-hand combat broke along the line, as Colonel George M. Edgar’s

Virginians futilely defended their position. A vicious brawl erupted around

the 26th Virginia’s colors, and by the time it was over, the flag

was torn from the staff, taken by 22-year-old Irish-born Corporal Terrence

Begley of Battery D, who was later killed at Ream’s Station. Four months after

his death, Begley received the Medal of Honor for his heroics at Cold Harbor.

All along the line, clusters of Confederate soldiers began

surrendering to the New Yorkers, raising white handkerchiefs and imploring the heavy

artillerymen to spare them. Standing near the color guard, Lieutenant Mather

watched in horror as a rebel aimed his rifle, firing it point blank into the

nearest Union soldier. When the Confederate threw down his weapon and said, “I

surrender,” the color guard offered him no mercy. The bearer of the flag (the

fourth one of the day) thrust the steel lance-head (which capped the top the staff) directly into the Confederate’s mouth, pinning him to the ground. As the luckless Confederate’s blood spilled onto the earthworks, the New Yorker snarled, “You

spoke too late!”

As the New Yorkers herded their prisoners to the rear—who

numbered in the hundreds—some of the more enterprising soldiers began turning Caskie’s cannon around to use them on the retreating Virginians. Captain

Kennedy, the commander of Battery L, put his shoulders against the wheel of one of the

abandoned guns. As he did so, a Confederate soldier emerged from a “rat

hole” (a nickname for a soldier-sized bombproof) and leveled his musket.

Lieutenant Mather promptly drew his pistol and fired, which changed the

Confederate’s mind. He threw down his weapon and surrendered.

For the next fifteen minutes, the 7th New York continued

to collect prisoners. So many of Edgar’s men had surrendered that the 7th

New York had to perform cursory provost duty to corral them all. With a dozen men,

Mather went from rat hole to rat hole, forcing frightened Virginians out from

their covers. As this prisoner-collection proceeded, it became evident that no

other troops had accompanied the 7th New York over the works. (Only

one other regiment, the 5th New Hampshire—a regiment that contained a mix of veterans, drafted

men, and substitutes—had entered Edgar’s redoubt.)

In the end, none of the promised reinforcements came to the assistance of the

New Yorkers. Lt. Col. John Hastings, the 7th New York’s second-in-command, complained, “The 7th

was in the advance, and was to be strongly supported. We advanced and carried

the works under a terrific fire, but no support came up.” Hastings, like many

others in his regiment, blamed Gibbon’s division (and a portion of Barlow’s

division alongside it) for failing to advance. The initial fire from Edgar’s

Salient had been so severe that Gibbon’s men had simply lied down and refused

to move. Hastings continued, “So disastrous was the fire that the oldest

veterans quailed before it and could not be urged forward.”

It didn’t take long for the Confederates to realize they

could take advantage of the 7th New York’s exposed position. With

alacrity, nearby reserves closed the hole opened up by the heavy artillerymen.

Brig. Gen. Joseph Finegan’s Florida brigade moved into the yawning gap at Edgar’s

Salient. When this new threat emerged, the New Yorkers discovered they possessed insufficient time to reform their lines, and as Lt. Mather related, “in our broken form we

could not resist them.” The New Yorkers fell back across the ground over which they

had earlier charged, and when they reached at the edge of the woods where they

had started, they found Gibbon’s division lying there, face down in the

grass with bayonets fixed.

Worst of all, during the retreat, the 7th New

York lost its colors. Sometime during the retreat, the last color bearer (the

one who had stabbed the surrendering Confederate in the mouth) fell dead. Frantic

in his efforts to recover the flag, Lt. Mather took his twelve-man squad and

went looking for it. But it proved to be a futile effort; it was too dangerous for Mather to keep his men between the hostile

lines. Battery L’s other first lieutenant, Thomas J. McClure of West Troy, New

York, returned to friendly lines around the same time as Mather, but with no soldiers under his command. Furious

that the colors could not be found and that McClure seemed to have lost an

entire section of the Battery, Captain Kennedy arose from his position behind

Gibbon’s men and began berating McClure. For several minutes, the two officers

stood quarreling. When bullets started to fall closely, Mather attempted to stop the argument, screaming, “Gentlemen, for God’s sake! Lie down!” He had just put his

hand on McClure’s shoulder when a case shot burst twenty feet away. A chunk of

metal the size of a human hand struck McClure in the arm, severing it, and then

it passed through the unfortunate officer’s chest, killing him.

The shrapnel didn’t stop there. The whirling piece of metal

exited McClure’s back and hit Captain Kennedy in the left thigh. Mather immediately

pulled out a handkerchief, and using a stray bayonet, applied a tourniquet to

Kennedy’s leg. Calling over two men, he ordered them to escort Captain Kennedy

to the rear. This was the last that Mather ever saw of him; Captain Kennedy left the field draped over the

shoulders of those two helpful soldiers. (Incidentally, Kennedy recovered from his wound, but he

was captured at the Battle of Ream’s Station, August 25, 1864. On September 10,

he died of the effects of typhoid fever at Libby Prison.) Then, gathering four men, Mather

commenced burying the shattered remains of Lieutenant McClure.

For the rest of the day, the fighting sputtered at long range. As most Civil War buffs know, the Confederates repelled all the June 3 attacks made by the

Army of the Potomac. The Union losses were so great that, in his memoirs,

Lt. Gen. Grant expressed regret for ordering it forward, saying it was the one

assault he wished he could take back.

Perhaps it is less well known that, in spite of the army-wide disaster, one of Grant’s regiments

had, indeed, broken the Confederate line. With characteristic élan, 7th New

York Heavy Artillery surged over Edgar’s Salient, routing the defenders.

Unfortunately, the reserve line under Brig. Gen. Gibbon didn’t rush in to assist the victorious heavy artillerymen. Grant’s one opportunity to exploit the breakthrough at

Cold Harbor evaporated because his most experienced soldiers, as a collective, refused to advance.

After the battle, Lt. Fred Mather expressed disappointment in those veterans. Mather’s regiment had done its duty, but the veterans in the second line had not done theirs. In Mather’s opinion, the veterans of the 2nd Corps had left the heavy artillerymen out in the cold. It had to be a

bitter feeling. Years later, Mather recalled, “It has been said that our

regiment was the only one that broke the enemy’s line that day; if so, we paid

dearly for that honor.”

Mather was right. The June 3 attack at Cold Harbor cost

the 7th New York 385 officers and men: 65 killed, 52 mortally

wounded, 197 wounded, and 71 missing.

While the rest of the Army of the Potomac went to ground, the

7th New York proved that it came to Cold Harbor to fight. No one could justifiably call it

a “band box” regiment ever again.

|

| Here's the modern day location of the 7th New York Heavy Artillery's attack of June 3, 1864. Like the Alsop farm engagement, this battlefield is presently on private land. |

No comments:

Post a Comment