For the past three posts, we’ve heard from survivors who belonged to

the unfortunate 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry, the regiment

captured at the Battle of the Wilderness. This last post will be told by one of the

officers who avoided capture (at least for a time).

On May 5, 1864, Second Lieutenant William H. Dieffenbach, a

24-year-old machinist from Perry County, found himself in a tight situation.

Dieffenbach commanded Company B, the company deployed on skirmish duty. During

the confusing engagement near the Permelia Higgerson farm, Dieffenbach’s

skirmishers became separated from the rest of the brigade. As the battle heated

up, Col. William McCandless charged forward with the 2nd, 7th,

and 11th Reserves, but before Dieffenbach’s skirmishers could catch

up with the line-of-battle, a Confederate unit interposed between them and the

rest of the brigade. The 2nd and 11th Reserves collapsed

and broke for the rear. Those regiments cut their way out of the trap, but in retreating, they

left the 7th Reserves surrounded. Dieffenbach’s men were nearly

caught as well. As Dieffenbach told it, “I tried to rally the battalion, but it

was no use. About 11 of my men were lost before I got out of the Wilderness,

which piece of strategy I accomplished about 4 PM after some of the gayest

maneuvering ever heard of in this army.”

That evening, as the Union 5th Corps reformed

west of the Lacy House, Lieutenant Dieffenbach called the roll; he discovered

that only 44 men from his regiment were present and accounted for. Some of these men belonged to

Company B, but a few others had been with the main body of the 7th

Reserves and fled when the regiment surrendered. In any event, the enlisted men

pointed out that Dieffenbach was now the only surviving officer. The small

battalion looked quite pathetic when McCandless called it into line the next

day, yet the band of survivors gamely stuck to the mission at hand, to

battle the Confederates until they surrendered. Although 86% of the regiment

was now captured, Dieffenbach’s men fought every day from May 6 to May 13.

Writing to his uncle, Dieffenbach reported, “For ten days we had been under

fire during the day, and either under fire or marching at night. I lost eight

gallant boys wounded out of the few I brought out of the first engagement, and

as for myself, I was completely ‘played out’.”

Lieutenant Dieffenbach commanded the 7th

Pennsylvania Reserves for eleven days. On May 16, Captain Samuel B. King, an

officer who had been on recruiting duty, arrived with a handful of men. By

virtue of seniority, King assumed command of what was left of the regiment.

Dieffenbach was glad when it happened: “I tell you, I was pleased to see him

come, for I am really tired of being Colonel, Quartermaster, Doctor, and

everything else myself.” Later on, two other officers arrived, both of them

having fled the Confederate provost guards. Bravely, they swam the Rappahannock River below

Fredericksburg to make their escape. This brought the officer contingent in the

7th Reserves up to four.

The loss of his regiment and the rigors of the Overland

Campaign forced Dieffenbach to question the tactics of the general-in-chief.

Dieffenbach lamented, “For my part I am tired, and want rest. I approve of

Gen’l Grant quelling the rebellion this summer, but he has been quelling it

entirely too fast for me during the last two weeks. I would rather he take

several bites at the cherry than try to swallow it whole.”

Thirteen days after writing those lines, on May 30, Dieffenbach

was captured at the Battle of Bethesda Church. As it turned out, he ended up

confined at Camp Oglethorpe, reunited with the other officers from the 7th

Pennsylvania Reserves, those who had been captured twenty-five days earlier.

If only Dieffenbach had managed to last one day longer. On

May 31, Maj. Gen. G. K. Warren read farewell orders to the division, and on

June 3, it left the front lines. Dieffenbach was captured in the 7th

Reserves’ very last battle.

On June 16, the 7th Reserves returned to

Philadelphia for muster out. It numbered only 53 officers and men.

The exact number of 7th Reserve soldiers who died

in prison is unknown. As stated earlier, 273 officers and men were captured on

May 5. Andersonville prison claimed the lives of 67 of those men, but 135 others died of non-battle causes. Presumably, many of

those men died inside Florence Stockade or other various other prison pens that held members of the regiment. If so,

incarceration may have killed 49% of the number captured on May 5.

Dieffenbach worried that Grant had tried to do too much, trying

to swallow the rebellion whole. In the process, the 7th Pennsylvania

Reserves got swallowed whole instead.

|

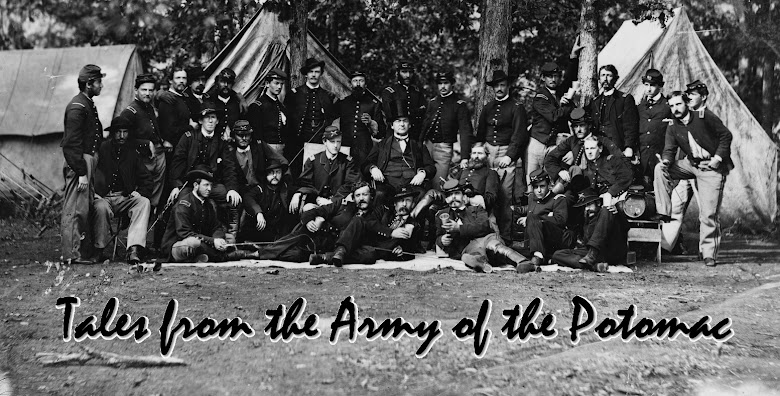

| This image depicts Company F, 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry. The officer in front is probably LeGrand Speece, who was captured on May 5, 1864. |

|

| This is Company H, 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry. Lieutenant Jacob Heffelfinger can be seen standing in front holding his sword. |

|

| This is Lieutenant William H. Dieffenbach, who commanded the 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry for 11 days after the entire field, line, and staff, were captured on May 5. |